Japanese Studies in “Intersubjectivity”

Professor Shigeto Sonoda (Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, The University of Tokyo)

I recently developed an enthusiasm for a certain research field. This is a field called “international psychology,” which I introduced last year in a public lecture I gave at the Institute for Advanced Studies on Asia, the University of Tokyo.

I became interested in the issue of social consciousness about international relations at the supra-national level of Asia when I participated in the AsiaBarometer Project led by Inoguchi Takashi, now Professor Emeritus of the University of Tokyo. This was an enormous project spanning six years from 2003-2008 with extensive social surveys conducted in as many as 32 countries. The accomplishments of this project won’t need my explanation here as many papers and books have been already published.

In midst of struggling with this gigantic data, I have realized several things.

First, projects of large-scale data collection, such as this one, create a data which is so big that it exceeds researchers’ explanatory capability. This contrasts with traditional research method where researchers first identify a problem and then proceed to create, collect, and interpret the data. I have felt powerlessness many times when confronted by the structure of data that cannot be grasped by frameworks believed to be utilized within the limits of our comprehensibility.

Second, almost as the flip side of above point, it becomes easy to sense the limit of the effectiveness of available explanatory frameworks. Many theories and explanatory frameworks do no more than generalization based on data that are known to the researchers and are explainable. On the other hand, when data becomes enormous, the limit and the effectiveness of old theories and explanatory frameworks become frequently clear. From here, what kind of inquiries can we tease out, and can we find good answers for these inquiries? We cannot escape from this kind of questions whenever we’re doing researches in the intersection between social sciences and area studies.

Third, it is extremely difficult to make sense of the answers to questions about relationship among countries researched.

Whenever results of public opinion surveys conducted by Genron NPO on Sino-Japanese relations are announced and explanation is required, experts are called upon to give comments and interpret the results. All kinds of comments are made every time, but it is rare, if ever, to verify them. When data about Japan is accumulated and data about other countries is also accumulated, however, it becomes necessary to find universal and systematic explanations for why those comments are possible. Needless to say, explanations like “Japan is what Japan is” simply won’t work here.

In fact, it is obvious that the answer for the question of how countries evaluate Japan cannot be found “inside” Japan.

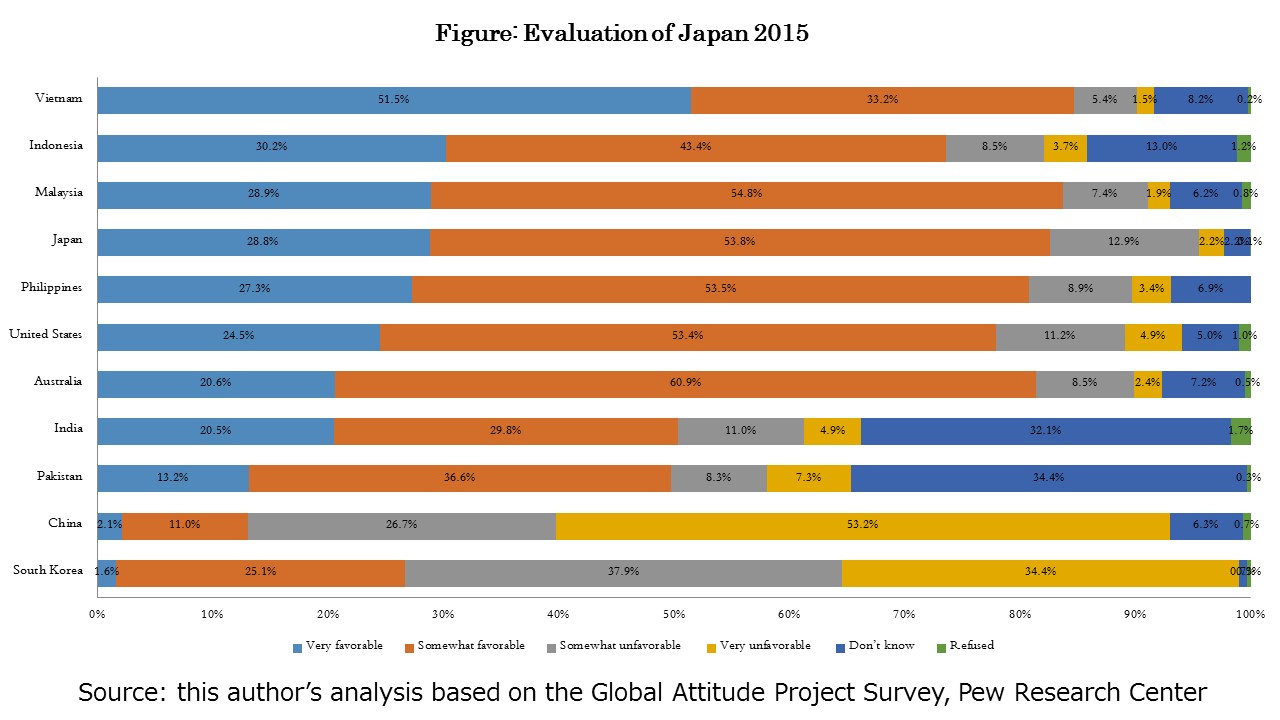

Fortunately or unfortunately, data continues to be accumulated worldwide after 2008 when the AsiaBarometer project completed. Besides Pew Research Center which accumulates and publicizes most widely and vigorously surveyed data, Asan Institute for Policy Studies in South Korea, Global Times in China, Japan-Taiwan Exchange Association in Taiwan, Social Weather Stations in the Philippines, and Lowy Institute in Australia all regularly conduct surveys on images of Japan. To interpret these survey data carefully and analyze the factors contributing to the formation of images of Japan will be an important research topic in the field of Japanese studies. Considering that images are formed in the realm of intersubjectivity, it is obviously necessary to analyze the side that looks at Japan.

Many inquiries in Japanese studies have developed from within the “relationship” between the research environment that trained Japanese studies researchers and the country of Japan. As such, their approaches and interpretations cannot be understood without taking into consideration the aspects of “intersubjectivity.”

In regions where images of Japan are bad, some particular types of research questions will develop out of this particular condition, while in regions where images of Japan are not bad different types of research interests might develop. To bring Japanese studies to a higher level, it is necessary to fully understand this kind of research configuration.

Pew Research Center survey contains more questions for China than for Japan in more targeted countries, which is an episode telling us the change of time.